In the years running up to the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. healthcare industry was thriving with growth and innovation. With steady and growing patient volumes, broad health insurance coverage and generally adequate reimbursement and funding, the focus was largely centered around reducing the total cost of care while improving access and quality.

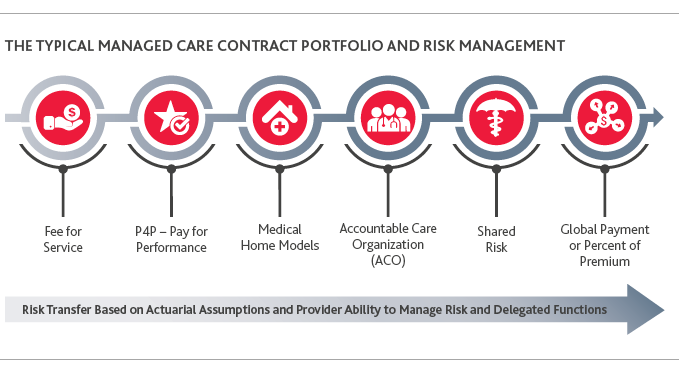

Across patient segments, coverage increased via managed care contracts and other third-party managed care arrangements. This landscape allowed providers and payers to develop and implement value-based payment models and other innovative agreements within their managed care contract portfolios. Everything healthcare organizations do is tied to the terms of these agreements—most importantly, how payment is received and how performance is publicly displayed via payer websites and report cards.

In fact, this “contractualization” of your patient base is central to understanding the importance of managed care contract portfolios, as in most major markets, 80-90% of patients’ coverage is via managed care contracts.

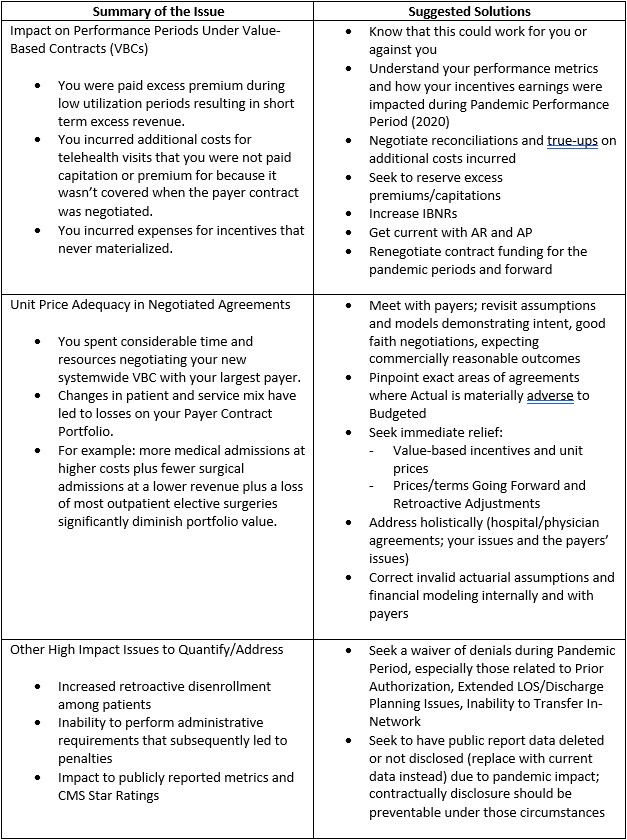

COVID-19 has fundamentally disrupted this landscape, and as we slowly begin to move forward, providers and payers must assess the impact on their managed care contract portfolios, understand emerging issues and then take steps to proactively address the new marketplace and reimagine their path forward.

The pandemic destroyed 2020 budget assumptions (and to some degree 2021, 2022 and beyond) on all levels: revenue, expense, case mix, service mix, occupancy, and importantly, an organization’s managed care contract portfolio and associated value-based care models. Each of these issues need to be considered in the context of contract portfolios.

While the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other payers incurred additional, non-budgeted expenses in 2021 related to COVID-19, there are many statistics that bear discussion about their impact to reimbursement and spending, across the portfolio of risk-based and fee-for-service based contracts:

Traditional Medicare spending was down 7% ($305B in 2020; $328B in 2019) with the most dramatic drop being between March and May 2020 when spending was down 48%. Spending for all between March-September 2020 was down 50-60%.

This created a windfall of profit for commercial insurers, triggering a series of state-mandated premium refunds to policy holders, additional benefits for members and additional reimbursement for providers. Additionally, U.S. federal relief programs pumped billions of dollars into providers and payers over the course of 2020 and into 2021.

Before March 2020, Telehealth visits represented less than .1% of CMS visits; for the period of March–December 2020, it rose to 16% of visits.

As often is the case, there were significant variances across the U.S. in major markets and in rural areas about spending trends and other COVID-19 related metrics.

The actuarial assumptions and financial modeling around utilization and unit price that payers and providers relied upon in formulating reimbursement methodologies, rates and incentive calculations are proving to be way off for 2020 and 2021. These actuarial assumptions are critical for a percent of premium, capitation and value-based care incentive arrangements. Examples include:

Consider capitated or percent of premium risk share portfolios; on one hand, being on a capitated or percent of premium reimbursement methodology during this time is good in that you are still getting paid for services based on pre-pandemic utilization assumptions. Simply stated, fewer people accessing elective services equates to low claims expenses which leads to higher margins. On the other hand, reimbursement for the costs of telehealth waived copays are in question.

A good example of the importance of the use of actuaries is in risk adjustment. The level of funding for Medicare Advantage (MA) plans is linked to risk adjustment scores and completion of member Annual Health Assessments (AHAs). These AHAs help capture the true risk score of the population of the MA plan, and the MA plans are paid by CMS on a risk-adjusted basis.

We knew early in the pandemic that the disruption to utilization patterns would have both a short-term and long-term impact to risk scores, risk adjustments, AHAs and other revenue and expense levers in healthcare. CMS recognized this early and moved quickly to mitigate the impact. One of the ways CMS achieved this is by allowing AHAs to be done via telemedicine visits. This means that the diagnoses documented in AHAs, and other face-to-face visits facilitated via telehealth, count toward the calculation of patients’ risk scores. A patient’s risk score is reflected in the reimbursement from the health plans retrospectively, so the risk score calculated from 2020 DOS directly impacts 2021’s reimbursement.

Similarly, the unprecedented shift in patient and service mix has rendered previously negotiated unit prices insufficient for most providers’ post-pandemic budget needs. Payers and providers alike recognize that the disruption in actuarial and other assumptions that are the foundation of current managed care contracts warrant changes in contract pricing structures, reimbursement methodologies and contractual terms.

From CMS Medicare Shared Savings, ACO and bundled payment programs to commercial insurer value-based care (VBC)/pay-for-performance (P4P) programs, these all contain initiatives (clinical or administrative) that are tied to performance metrics, time periods and economic consequences. The pandemic has disrupted providers’ and payers’ ability to manage these programs. As a result, providers may not be able to achieve performance and comparisons to prior-period performance as metrics have become less credible.

Providers’ inability to satisfy performance metrics will adversely impact value-based compensation. CMS has made a couple of important updates related to their VBC/P4P models because of COVID-19:

Under the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Advanced (BPCI-A) model, participants had two options: eliminate both upside and downside risk for 2020 by forgoing any reconciliation in 2020, or if they wished to remain in two-sided risk, BPCI-A participants could exclude from reconciliation clinical episodes with a COVID-19 diagnosis during the episode. As a result, the participants needed to perform significant analytical AI work to determine which option would be best for their program.

For those in the NGACO model, CMS made several accommodations available:

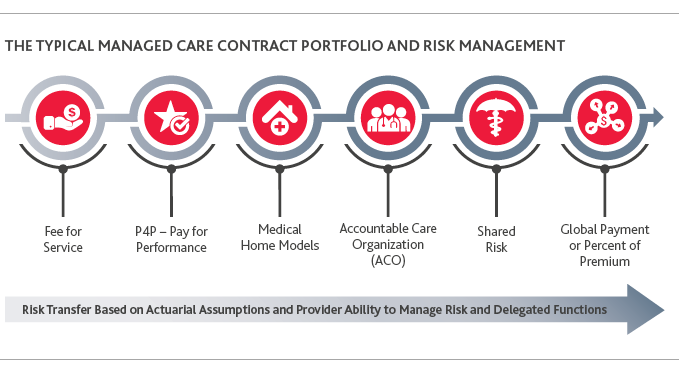

Below is an example of a 2020 Income Statement of a Commercial ACO, buoyed by both a drop in expenses and an increase in premium/capitation:

Given the lag between performance and payout, the financial consequences may not be immediately obvious and will likely show up on financial reports later. Providers may feel this impact across multiple years, as many value-based care agreements are multi-year, with considerable revenue and reimbursement tied to year-over-year performance improvement.

Payers and providers spend a significant amount of time and energy negotiating contract terms. Often, agreements between large payers and providers can take over a year to complete, and the terms of these agreements are increasingly becoming long-term. A 3-year term of agreement is today’s standard, but 5 and even 10-year agreements are becoming the norm.

These agreements represent assets that are meant to be maximized. Final financial and VBC/P4P terms in these agreements reflect an aggregation of dozens of methodologies and calculations, driven by actuarial and other assumptions on volume and service mix. The result for providers and payers is pricing terms that meet their financial needs. The pandemic has upended service mix, volume and stop loss pricing assumptions to name a few.

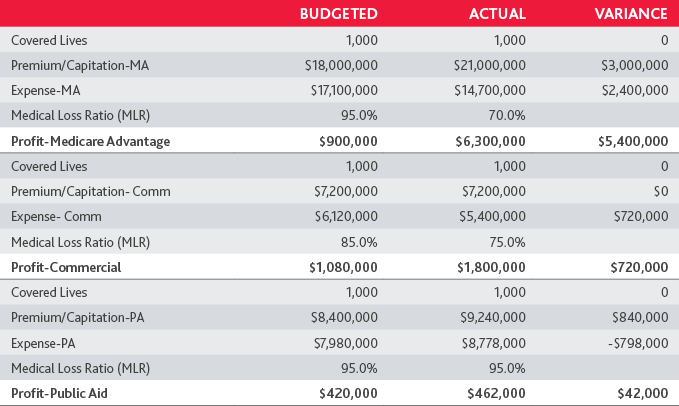

For one hospital, the impact of COVID-19 on their commercial managed care contract portfolio was as follows:

Because of the change in volumes, service mix, and other underlying assumptions that produced the current pricing terms in existing managed care contract portfolios, organizations may need to go back to the negotiating table to address unit prices that may no longer be sufficient for the “new world” budget needs (volumes, cost, mix of services, site of service changes). This new reality can apply equally to either a provider or a payer, but the reaction may be different depending which side of the new reality you are on.

The full extent of the pandemic’s impact on employment has yet to be seen. We expect the percentage of the population covered by health insurance will fluctuate greatly over the coming year. For some patients, their coverage may change multiple times within a plan year or shift from employer-based coverage to coverage through Medicare, Medicaid, or the Affordable Care Act’s health insurance marketplaces. These market factors likely affect providers’ payer mix and lead to increased retroactive adjustments to claims, eligibility, capitation and incentive earnings.

For example, monthly capitated payments are retroactively adjusted for changes in membership, with some changes going back 90 days or more. Even the fee-for-service arrangements will not be completely immune from the impact of retroactive disenrollment as payers may seek to recover claims paid for patients who were retrospectively determined to be ineligible for coverage.

In addition to these managed care contract portfolio valuation considerations, there are several other emerging transformative forces in healthcare as we move into a “post-pandemic” era:

On January 1, 2021, CMS implemented the Price Transparency of Hospital Standard Charges regulation. The regulation’s purpose is to make it easier for consumers to shop and compare prices across hospitals and estimate the cost of care. The regulation requires hospitals to provide clear, accessible pricing information online about the services in two forms: a machine-readable file with all items and services, and a consumer-friendly format of shoppable services. This is a major issue that not only impacts hospital operations, but also brand reputation and relationships with stakeholders.

SOS has become an area of emphasis among payers before, during and after the pandemic. Payers are increasingly leveraging this tactic to drive care to lower cost sites of care, especially and specifically: lab services, imaging services and elective surgeries. Significant savings accrue to payers (including employers and patients) by directing services to these lower cost SOS whenever possible. Hospitals do not fare well under SOS changes on their own. Payers have implemented policies that require prior authorization and proof of medical necessity for providing these services in the hospital-based setting (i.e., MRIs, surgeries). Physicians and hospitals have new opportunities to work together to take advantage of this trend by creating ASC joint ventures, creating incentives to increase its utilization of ASCs, and exploring joint- contracting strategies around SOS (i.e., Shared Savings for re-direction of services to lower cost settings).

At every level, we are becoming both more aware and more activated to change the differences in access to healthcare, and the quality of care received, across communities. COVID-19 further exposed and detailed these inequities, especially in its impact to African American and Latinx populations. Reducing healthcare disparities is becoming a major focus for healthcare payers and providers. One recent example of this is from HealthCare Service Corporation (HCSC), one of the largest payers in the USA, that announced it is investing $100M in 2021 to develop and implement community-based strategies to improve health equity.

Telehealth represents the future of medicine. The rapid rise of telehealth because of COVID-19 has become the new “standard visit.” It’s amazing to consider the opportunities of tele/virtual health when integrated with patient portals, wearables and other transformative forces accelerated by the pandemic to create a new connection with patients.

A healthcare organization’s managed care contract portfolio represents any provider’s largest source of revenue, profit and volume. These assets need to be reassessed for impact, reinvestment and strategic reaffirmation as we move into this new post-pandemic world. As providers assess changes in their landscape and plan for economic recovery, providers would be well-served to proactively update their managed care contracts, but more broadly, revise their overall managed care strategy.

Providers should assess their managed care contract portfolio and quantify all the risks. Based on that assessment, many providers will likely realize they need to open their managed care contracts for renewal negotiations to secure needed cash flow and reset pricing. When a negotiation makes sense, the provider should focus on addressing radically changing healthcare economics, optimizing reimbursement and securing appropriate contractual protections. Simply seeking rate increases is likely to be a shortsighted and unsuccessful strategy. Rather, providers should consider how their current reimbursement model might be reevaluated in the context of their managed care contracts.

For example, considering the impact the pandemic had on the industry, providers should ask whether a fee-for-service arrangement is still right for their organizations or whether alternative reimbursement methodologies would be more appropriate. These methodologies may not only offer cash flow stability on a short-term and longer-term basis, but may also mitigate against risk relating to significant shift of patient mix and services. Such an evolution in reimbursement will necessarily impact other contractual provisions such as term, termination, audit rights, prompt pay and offset and similar provisions.

COVID-19 created significant cash flow impacts for providers. In addition to Provider Relief Funds (PRFs) available from the federal government, several national commercial payers have offered accelerated or advance payment programs for providers. While not all payers have formal programs, many are willing to work with their providers to craft a customized, provider-specific relief plan. Feasible options will be partly determined by the type of provider entity and the type of managed care contract held by the provider and could be in the form of future premiums, incentive accruals or estimates, current accounts receivable, or zero- or low-interest loans.

Providers may also consider other potential sources of financing by leveraging provider organizations, such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Clinically Integrated Networks (CINs), and Management Service Organizations (MSOs), among others. Many ACOs and CINs already had agreements in place with payers for shared savings or other value-based arrangements. They are in an ideal position to secure accelerated payments or advances from payers on behalf of their participating providers. Seeking new or maintaining existing affiliations with risk-bearing provider networks is also a way for providers to seek additional revenue stability and obtain access to a more stable patient base. A further advantage of an ACO is the ACO’s ability to utilize Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statute waivers providing immunity from prosecution under these laws. These MSSP ACO waivers will survive the end of the public health emergency and can be used to create pro-Triple Aim incentive payments beyond current regulatory limits.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put telehealth and other remote care services (e.g., medical homes and remote care management) in the limelight. Stakeholders are predicting that a widespread adoption of telehealth and remote care services by patients and payers is now inevitable. Many payers have also been more willing to reimburse telehealth and remote care services. As providers consider requesting payers to add telehealth and remote care to their managed care contracts, they must have a solid understanding of the economics of such services, including market rates for managed care reimbursement and typical provider margins. To successfully implement these alternative remote care services, providers should strategically turn their existing telemedicine and remote care capabilities into full virtual health workflows and engage and activate their patient base to leverage virtual health options.

The trend toward greater retroactive disenrollment could especially impact capitated and other risk-bearing providers in addition to fee-for-service arrangements. Given that such retroactive adjustments are likely to exceed normal levels and could result in severe provider financial stress, providers should seek to limit their risk related to future retroactive disenrollment, to the extent permitted by law, such as by limiting lookback periods, clawback rights and other similar repayment terms.

Looking ahead, the pandemic has highlighted the need for providers to build in contractual protections for the pandemic and other national and local emergency events (such as floods and hurricanes). These events materially and adversely impact cost, access to services and patient volumes. The structure of these provisions will depend on the overall economic model of the payer-provider relationship. By way of example, current force majeure clauses may not be designed to excuse performance temporarily or even permanently in response to this pandemic or other emergency events. Therefore, providers will need to analyze their contractual rights and obligations under each managed care contract with respect to these emergency situations.

Payers and providers are likely to have significantly different views on what contractual modifications should be implemented to address their mutual needs during the post-pandemic recovery. Accordingly, the industry is primed for a round of contentious contract renegotiations—many off renewal cycle—as health systems, hospitals, physician groups and payers attempt to adapt to new financial realities.

The year ahead may look uncertain, but that doesn’t mean you delay key decisions. Certainly, payer contracts are among your highest value assets to maximize, and we will continue to see the trend of “contractualization” of patient bases, increasing the importance and value of those contracts.

For providers exploring managed care contract portfolios in the new world order, consider how they fit within your organization’s strategic plan through the following pillars:

In addition to understanding your strategic plan, consider your managed care contract portfolio through the transformative forces that are at play in today’s healthcare system—from digital transformation to addressing healthcare disparity. As we move forward, think big picture and proactively look at managed care contract portfolios in the context of a broader “strategic refresh."